Sanctions for breach of an Anti-Social Behaviour Injunction – an update

- Details

Tim Jones considers Court of Appeal guidance on sanctions for breaches of Anti-Social Behaviour Injunctions.

In a previous article (link here), I discussed a report by the Civil Justice Council (“CJC”) on the effectiveness of the civil injunction regime under Part 1 of the Anti-Social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014 (“the 2014 Act”).

One of the issues raised by the CJC report was that County Courts were experiencing difficulties in imposing appropriate sanctions for breach of anti-social behaviour injunctions (“ASBIs”).

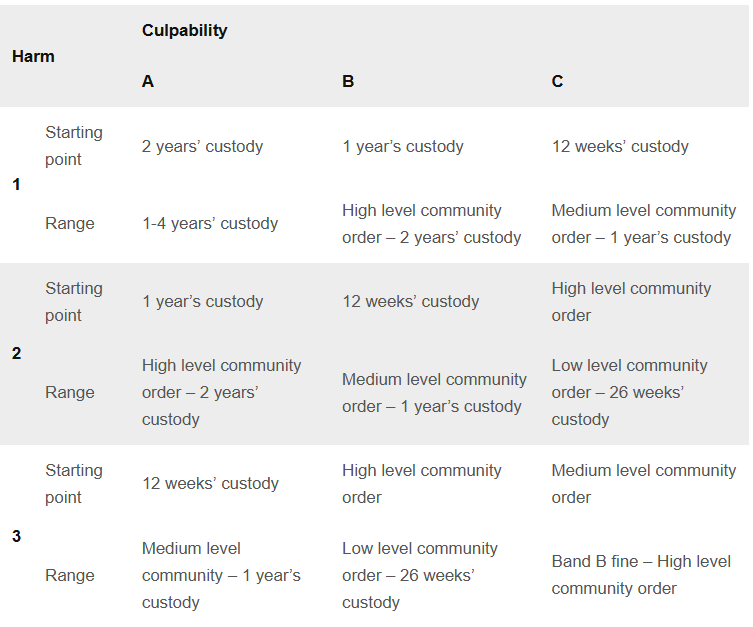

The County Court’s powers to punish breaches of such injunctions is limited to fines of up to £2,500, imprisonment of up to two years [1] or sequestration of assets. [2] There are no Sentencing Council guidelines for breach of an ASBI, and the Court of Appeal in Amicus Horizon Limited v Thorley [3] had said that courts should follow the guidelines for breaches of anti-social behaviour orders (“ASBOs”) (which are now subsumed within the guidance for breaches of Criminal Behaviour Orders). The table from the sentencing guidelines is set out below:

The problem with asking the County Court to apply the CBO breach sentencing guidelines is that they are based on the assumption that the court can impose community sentences and custodial sentences of up to five years, whereas the County Court does not have the power to do either of these. The CJC found that this had led many judges to impose suspended custodial sentences in less serious cases simply because the alternative was making no order whatsoever – after all, it was unlikely, in most cases, that the Defendant would have the means to pay a fine or assets to sequester. This is in spite of case law that says that a suspended custodial sentence should only be imposed if the custody threshold is met to begin with [4], and not simply because the Defendant lacks the means to pay a fine. [5]

The CJC report stated, at paragraph 383, that:

“There are three objectives to be considered when dealing with the breach of an order under the 2014 Act: the first is punishment for breach of an order of the court; the second is to secure future compliance with the court’s orders if possible; the third is rehabilitation, which is a natural companion to the second objective.”

Enter the Court of Appeal

On 16 December 2022, the Court of Appeal considered these issues in the case of Lovett v Wigan Borough Council, Smith v Network Homes Limited and Hopkins v Optivo.[6] In that case, the Defendants had been sanctioned as follows:

- Ms Hopkins’ breach consisted of causing alarm and distress to her neighbours through loud banging noises, shouting, slamming doors and shouting and fighting with her partner outside her home. She was sanctioned with 28 days’ imprisonment suspended until 29 April 2023 on condition that the complied with the injunction going forward. One of her grounds of appeal was that her sentence was excessive.

- Smith was found to have breached a term of an ASBI which prohibited “swearing, shouting, banging, playing amplified sound, or causing any other noise nuisance at [his home], so that it could be heard outside [his home].” 31 breaches were alleged at first, but this was reduced to ten, nine of which consisted of loud music, sounds, or shouting, and one of which consisted of singing and loud conversations. The judge found nine of the ten allegations proved and made an order committing him to prison for 12 weeks, suspended for 12 months. One of his grounds of appeal is that the court should have considered making a possession order in the alternative to committal, which, he said, was disproportionate.

- The injunction against Mr. Lovett prohibited him from engaging in conduct likely to cause nuisance, annoyance, alarm or distress to any person in the neighbourhood, and a further term was later added excluding him from an area which included his home between the hours of 6:00pm and 9:00am. By the time he came before the court in relation to the most recent allegations, he had already been found to have breached the injunction 177 times, and he had been committed to prison at least four times between 2017 and 2021; indeed, at his latest contempt trial, he appeared by video link from prison. The latest tranches of breaches related to 21 occasions on which he had been in his home overnight, and he had been sentenced to a further 30 weeks of custody to run concurrently with the custodial sentence he was already serving.

It should be noted that Mr. Lovett’s grounds of appeal related to the findings of contempt themselves rather than the sentence imposed, and so I will make no further mention of his case here.

The principles

Birss LJ observed a difference between the applicable principles for sentencing in criminal cases and sanctions for contempt, and thus rejected any suggestion in paragraph 383 of the CJC’s report that punishment came first in the order of priority as opposed to securing future compliance, and also said that the Sentencing Council guidelines should be treated carefully:

“33. A key difference is that the objectives underlying penalties for contempt are different from those in crime, at least in the sense of the relative significance of punishment as compared to ensuring future compliance with the order. We refer to paragraph 8 of the judgment of Coulson LJ in Breen v Esso Petroleum [2022] EWCA Civ 1405 with which we agree. This places the emphasis in civil contempt case on the importance of the objective of ensuring future compliance. We refer also to the very recent Cuciurean v Secretary of State for Transport [2022] EWCA 1519 (17 November 2022) and the judgment of Edis LJ at paragraphs 103-108 which also highlights Breen and draws attention to the fact that the statutory purposes of criminal sentencing established by section 57 of the Sentencing Act 2020 do not apply in the contempt jurisdiction (compare paragraph 38 below to s57(2)).

34. It follows that the passage in the CJC Report at paragraph 383 which may have been derived from the Sentencing Council guidelines, and could be understood as putting the objective of punishment first in the order of priority, ahead of ensuring compliance, is not right. Moreover the parts of the CJC Report (e.g. Annex 1 first paragraph) which propose that judges undertaking the task of sentencing for contempt regard as relevant the guidance produced by the Sentencing Council, must be treated with care.”

Birss LJ went on to set out the following principles:

- Save in special circumstances (e.g. when the breach itself is a criminal offence), the Sentencing Council guidelines can only be relevant in “the very broadest and generalised sense”. Birss LJ noted that the maximum penalty available to the civil court was far shorter than that for a criminal breach of a CBO (two years vs five years), and said that, in general, a civil contempt sanction that exceeded the severity that the sentencing guidelines would have led to was likely to be wrong.

- Amicus v Thorley had recommended the use of the then current sentencing guidelines for breaches of ASBOs, which predated the CBO sentencing guidelines and differed from them, and the court was now in a different position having had the benefit of adversarial argument on the point and the CJC report.

- The objectives for breaches of ASBIs were, in order of priority, as follows:

- Ensuring future compliance with the order

- Punishment

- Rehabilitation

- Suspension and adjournment may also provide an occasion for amendments to the injunction itself, as well as an opportunity to impose a variety of conditions, such as including a positive requirement under Section 1(4)(b) of the 2014 Act.

- The maximum term that can be imposed is two years’ imprisonment. One half of the custodial term will be served in prison before automatic release (Section 258 Criminal Justice Act 2003). Time spent on remand is not automatically deducted, so, if credit is given for that, consideration should also be given to doubling the period deducted to take Section 258 CJA 2003 into account.

- The concept of a custody threshold is relevant, and custody should be reserved for less serious breaches where other methods of securing compliance with the order have failed.

- Totality should be taken into account rather than simply adding up penalties for each individual breach, which would be likely to lead to an excessive total sentence.

- If custody is appropriate, the length of the sentence should be decided without reference to whether it should be suspended.

- The court retains the option of adjourning for consideration of sentence, which the court can use as an opportunity to speak directly to the contemnor about their behaviour. An indication of what sentence would have been imposed if the matter had not been adjourned is likely to be appropriate, together with a clear statement of what the consequences of good or bad conduct in the intervening period will be. The clarity of a statement about consequences is vital and it is important for judges to avoid making representations they did not intend to make.

- Considering the degree of harm and culpability, as per the Sentencing Council guidelines, was relevant.

- Having identified culpability and harm, the court can then adjust the sentence by taking into account additional elements which increase or decrease the seriousness of what has happened or amount to personal mitigation. It was impossible to identify all the aggravating and mitigating factors, but history of disobedience and the vulnerability of victims would be aggravating factors, whereas genuine remorse, ill health, age and lack of maturity might be relevant, as would an early admission of guilt.

- Reasons for making adjustments from a starting point should always be identified and their impact explained, albeit briefly. Cogent reasons should be given for going outside of the indicative range.

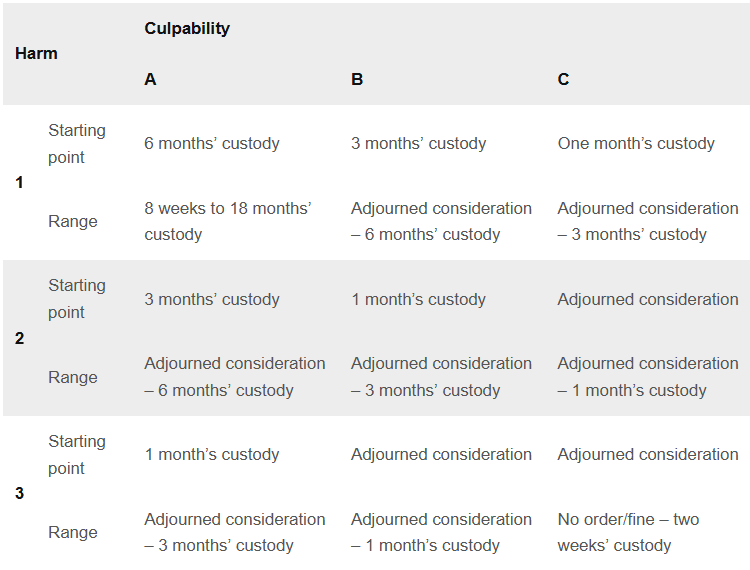

- The court approved the CJC’s proposed grid as set out below:

Finally, the court emphasised that this approach was concerned with breaches of orders under Part 1 of the 2014 Act.

Application to the particular cases

Hopkins

At first instance, the District Judge found that this was a category B2 case, adjourned sentencing for six months, but indicated that the sentence she would impose if not adjourning would be 28 days’ imprisonment suspended for six months. The Court of Appeal noted that the District Judge had reached this figure by treating six weeks’ custody as the starting point, when, in fact, it should have been 12, though this may have been influenced by scaling between the five-year and two-year maxima.

The Court of Appeal found that the District Judge had been “plainly right” to adjourn sentencing for six months, but the sentence that she indicated she would have imposed had she sentenced on that day was too severe. The District Judge was wrong to find that it was category B2 as there was a single admission of breach of the order, that breach caused minimal harm, and the remaining allegations had been dropped by the Claimant, meaning the level of harm could not be considered more than “light” as per category 3. Adjourning for consideration should have been the starting point, and an appropriate indication would have been that no order would be made provided no breaches were committed in the meantime.

Smith

The Court of Appeal was not persuaded that the District Judge should have considered making a possession order in the alternative to imprisonment, as these were not possession proceedings.

As regards the length of the custodial sentence, the Court of Appeal found that the Deputy District Judge at first instance had been right to categorise the case as B2 but wrong to apply the Sentencing Council guidelines directly, given the disparity in sentencing powers between the civil and criminal courts, meaning that an inappropriately high starting point of 12 weeks’ custody had been applied.

Commentary

The Court of Appeal has provided welcome clarity and guidance on the issue of sanctions for breaches of ASBIs. In my view, as stated in my previous article on this topic, the CBO sentencing guidelines were not fit for purpose for the reasons outlined by the CJC and by the Court of Appeal.

Using contempt hearings as an opportunity to amend the original injunction, including by using positive requirements, is a creative approach that goes some way towards compensating for the lack of a power to impose a community sentence. However, I wonder how frequently positive requirements will be used in practice, given that they are relatively rare to begin with and the requirement for a supervisor will still need to be met.

Mr. Smith’s argument that the court should have considered making a possession order instead of imposing a custodial sentence once again raises the philosophical question of which is more draconian out of eviction and imprisonment, but in my view, the fact that the Court of Appeal in Birmingham v Stephenson [7] specifically said that landlords should consider injunctions in the alternative to possession proceedings as part of the proportionality exercise under the Equality Act 2010 strongly suggests that the law considers eviction to be more serious in this context.

Given that the Court of Appeal specifically said that the aforementioned guidance was only supposed to apply to breaches of injunctions under the 2014 Act, it will be interesting to see what bearing, if any, it has in respect of breaches of injunctions under Section 3 of the Protection from Harassment Act 1997, nuisance, or tenancy breaches, as such conduct is often of the sort that would constitute anti-social behaviour for the purposes of the 2014 Act.

All views are my own.

Tim Jones is a barrister at Lamb Building.

[1] Section 14 Contempt of Court Act 1981.

[2] Section 38 County Courts Act 1984; Rose v Laskington [1990] 1 QB 562.

[3] 2012] EWCA Civ 817.

[4] Hale v Tanner [2000] 1 WLR 2377.

[5] Crystalmews Limited v Metterick [2006] EWHC 3087.

[6] [2022] EWCA Civ 1631.

[7] [2016] EWCA Civ 1029.